Raising Hare: A Memoir by Chloe Dalton

“When it comes to cool Pandemic projects, you win!” said the host of The Book Show podcast, Joe Donahue.

Raising Hare is such a good book! Chloe Dalton adopts a tiny baby hare (a whole different species from bunny rabbits), not to become a pet, but because she is afraid that if she doesn’t, it will die. She wants to let it live in the wild, so she avoids handling it as much as possible. She has no idea how to care for a hare and finds there is little help available to her in books or from experts. Most of the information out there focuses on killing and eating hares, not on feeding and keeping them alive. At one point, she finds some hints on what food to give them from a poem written centuries before.

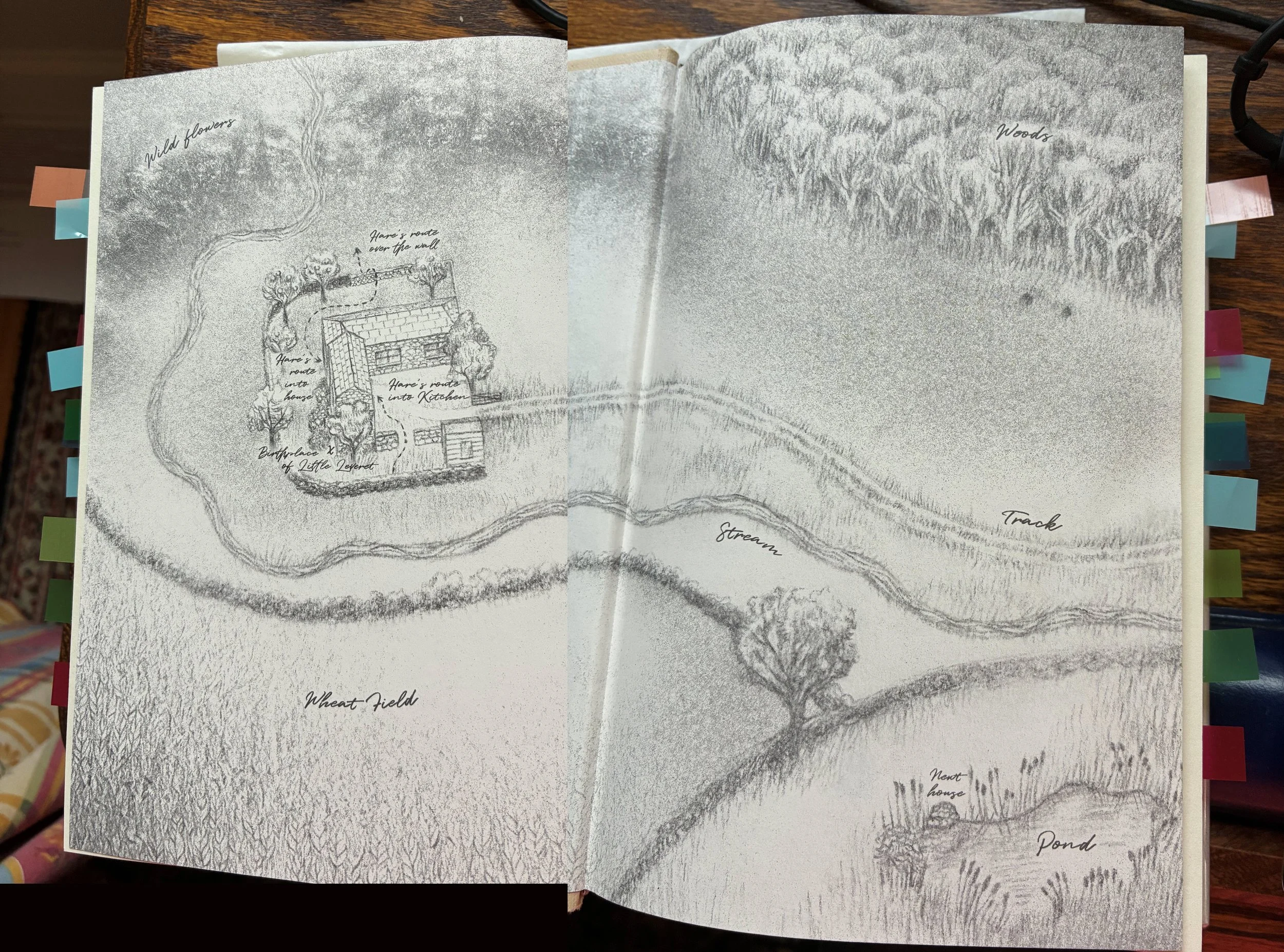

In the process of raising the hare, Dalton changes her own life and way of living. She lives in a simple house in England and, to allow the hare the freedom to live outdoors, she makes her home accessible to the outdoors. She keeps her garden (what the British call their yard) and surrounding land wild with plants and areas hares can use for food, shelter, and protection.

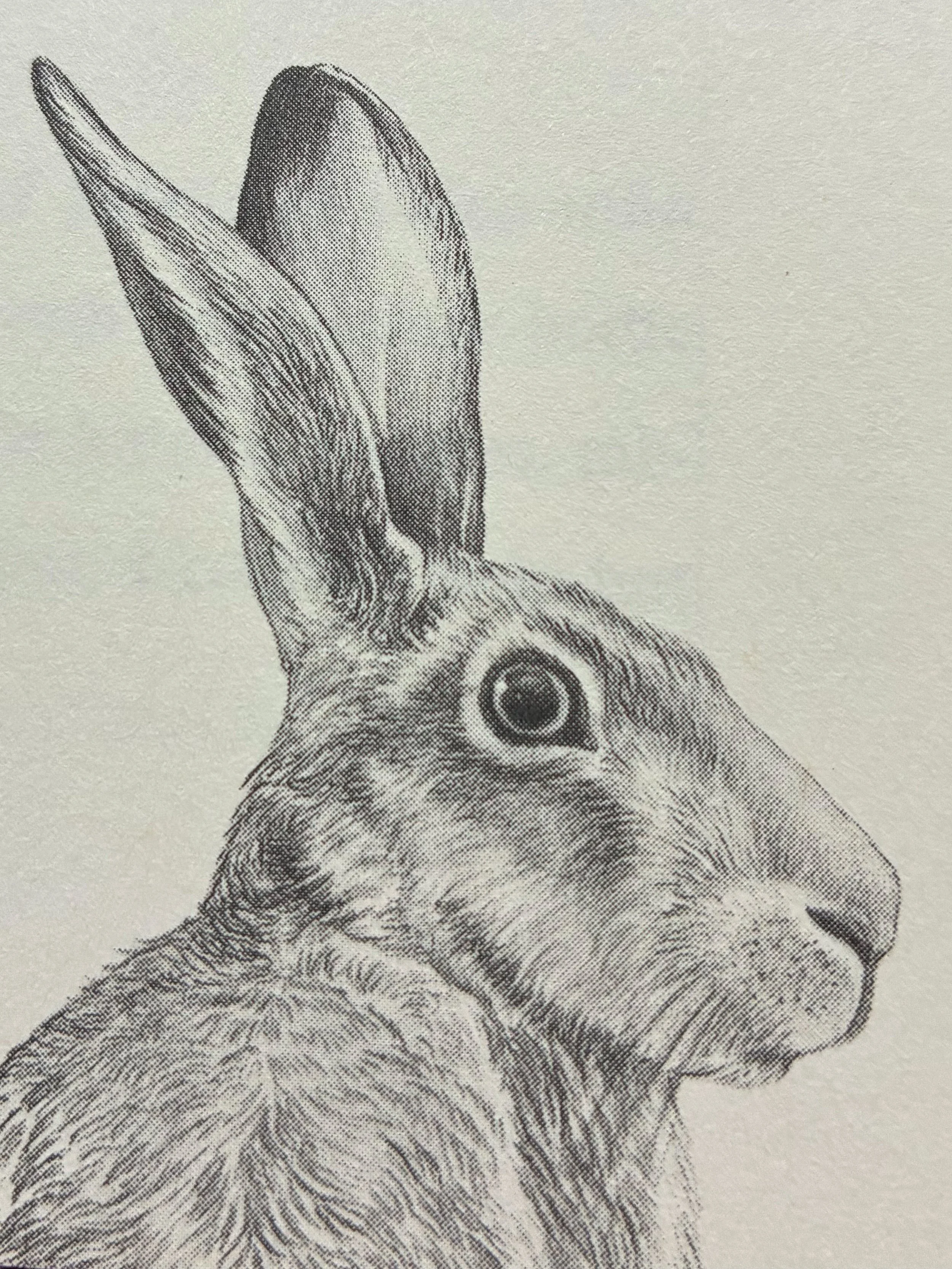

The book reminded me a little of H is for Hawk, another book I enjoyed about human interaction with a wild animal. Raising Hare is a story, a memoir, and engaging on that level. While appreciating Dalton’s story, watching her evolution, you also learn about hares. Turns out they’re very interesting! I loved the pictures, too, drawings of hares by Denise Nestor. And I adore hand-drawn “picture maps,” like the one on the endpapers of the edition I read.

Dalton’s adventure with the hare began with the pandemic shutdown. She was a political advisor:

I developed ideas and strategies for public figures, helped put their thoughts into words, and stood by them in the “war room” in a crisis. (page 17)

Her job involved a lot of travel, and she confessed to an addiction to “the adrenaline rush of responding to events and crises.” Dalton mourned the forced loss of that adrenaline-stoked life and “a baby hare had no place in any of the scenarios…I had envisaged for myself.”

I kept thinking of Padraig O’Tuama, one of my favorite writers/poets. He is from Ireland and often writes about his love of hares, both as wild animals and as mystical figures. Dalton, too, writes about the hare’s association with witchcraft and the supernatural.

From my own observations of the leveret [the word for a baby hare], I could think of many reasons why hares might have acquired such negative connotations. They are most active at night, and many other nocturnal creatures—like cats—have been traditionally associated with the dark acts of witchcraft. They can stand on their hind legs and leap vertically in the air, both of which might, from afar, look like the hare was walking. Their silence, watchfulness and acute hearing, combined with their uncanny speed and ability to elude hunters, give them an air of the supernatural. They are quiet but cry out when killed, which brings to mind folk tales about the mandrake root, supposedly inhabited by spirits that shriek if the plant is uprooted [Harry Potter, anyone?—mm]. They are wild, but often live in arable land in proximity to humans, making them both familiar and mysterious. They are long-limbed and beautiful, elegant and languorous—in short, they have some “feminine” traits, and therefore it is perhaps unsurprising that they are tarred with some of the same stereotypes that have clung to women across cultures and ages. (pages 92-93)

She writes about the many ways her daily life changed.

I had been bewildered by the responsibility of raising the leveret, captivated by its endearing ways, stirred by its mysterious nature and thoroughly inconvenienced by its dogged presence. For months, I had risen at dawn to make up bottles of milk or lay out food for the leveret. I had tiptoed around my house in the daytime so that it could sleep, and changed my own sleeping patterns, going to bed with nightfall. I had imposed on family and visitors the requirement to talk quietly and not frighten the young hare. I had avoided switching on lights at dusk, so as not to interfere with the leveret’s rhythms, and I had stopped using them in the garden, conscious for the first time of their disruptive effect on the vision of nocturnal animals. I had not worn perfume for months, imagining it to be caustic and disorienting to a hare’s sensitive nose, and no longer turned on the television for the evening news, to avoid subjecting the leveret to loud and discordant noises. Every day I chased out fat bluebottles that flew in through the ever-open sitting-room door, and once came back to find a startled partridge that shed feathers like an exploding pillowcase as I tried gently to usher it out of the house. I had even become reluctant to walk across the fields in daytime out of a desire not to disturb other sleeping hares. It was excessive. It was absurd. It was beautiful. (pages 118-119)

It was fun to read all the things Dalton did to keep alive and protect “her” hare, that hare’s offspring, the offspring’s offspring, and other hares and animals in the area. She enlisted the help of neighbors and friends to work toward “an environment that is safer for hares and other creatures of the land, wherever they may live, not at the expense of humans, but in balance with our priorities.” (page 266) At one point, she talked about farmers beginning to leave a small strip of land uncultivated, giving the animals a place to thrive at the edges of their fields. It reminded me of the Bible stories and verses in which Israel is told to leave a small amount of grain when they harvest the fields so that poor people can glean it.

After the long, interesting, and delightful story of all the months and years living with and tending to the hare, Dalton reflects a little on the way the hare changed her.

She has taught me patience. And as someone who has made their living through words, she has made me consider the dignity and persuasiveness of silence…She made me re-evaluate my life, and the question of what constitutes a good one…She did not change, I did. I have not tamed the hare, but in many ways the hare has stilled me. (pages 274-275)

I encourage you to read this book, whether you are an “animal person” or not. I am not, not particularly. I have no desire to own a pet, although I am happy for the joy they bring to my family and friends who do have pets. I love seeing animals in the wild and have been thrilled that our house here in the Pacific Northwest has a creek behind it and large back and front yards that have given us peeks of more birds and animals we had in the past. I am intrigued and curious about animals, as I think most of us are. This book gave me hours of happy reading. I think you will like it, too.

Raising Hare: A Memoir, by Chloe Dalton. Copyright 2024. Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.